The downfall of Danone’s – learning for dairy industry new entrants

The downfall of Danone’s – learning for dairy industry new entrants

India is the largest producer and largest customer of dairy products in the world. India accounts for about one-fifth of global milk produced. India is followed by the US, China, Pakistan and Brazil. In 2018, India produced 186 million metric tonnes of milk, or approximately 410 billion pounds, accounting for 22 percent of global milk production. Almost all of that is consumed domestically as a result of India's light diet, which includes creamy curries, yoghurt drinks, and a specific type of butter known as Ghee. Before we go any further, please keep in mind that this includes buffalo milk, which is an important source of milk in many developing countries. The truth is that milk is extremely popular in India. Danone, a French dairy company, hoped to capitalise on this in 2011 by establishing a division in India. Danone opened a processing plant in Haryana in an attempt to capture some of India's 1.2 billion milk consumers. Danone, on the other hand, closed its dairy business in India less than a decade later In the same year, the company earned $28 billion worldwide and ranked third among the world's dairy companies. With all this success, elsewhere, why did Danone's dairy business go wrong with all this success, elsewhere, why did Danone's dairy business in India go wrong?

Why does Danone’s dairy division fail in India?

Let us begin with some background information on Danone. Their activities are classified into three categories:

- Specialised nutrition like supplements and formula for babies;

- bottled water and gas water and

- Dairy and Plant-based alternatives

Dairy and Plant-based alternatives make up over half of Danone’s global sales, but it is also the ones that failed in India. Danone continues to sell specialised nutrition products in the country, but those sales are not broken out separately. Oh, and this is the same company as Danone in the United States. The company decided to rebrand in order to distinguish the spelling for American consumers.

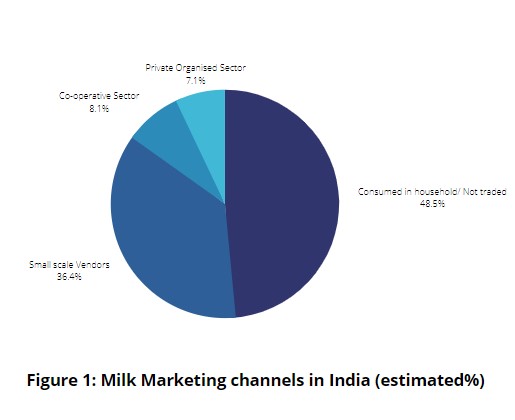

Anyway, here's some background information on India's dairy industries. In India, there are approximately 75 million dairy farmers. The majority of them are women who own one or two buffaloes or cows to supplement the family's income. Nearly one of half of India’s milk is not distributed rather consumed by the farmers household. This makes India’s dairy more fractured and localised than other countries Danone operates.

Taken the company's native France and one of its most important customers in the United States. Each has fewer dairy farms with herds that dwarf India's annual average of one or two. This was Danone's first problem in India. Sourcing milk is difficult for the half of farmers' households that do not consume it. Only about 15% goes to large organised corporations or government-run cooperatives. The remainder will ping hundreds of small local milk processors.

“So they are not very large farms which are out there from where you can go and just source the raw milk. But there are local companies who have very deep strongholds in that particular area where farmers have this commercial understanding with these people over years or decades. They will sell to them” Harminder Sahni- Founder Wazir Advisor

“ Milk in that way, or dairy products in that way do well over the long run. And that’s what Amul has done, that’s what mother dairy has done because they’ve built that infrastructure over years. Versus having to do all of that by yourself. You would never be able to match the volumes that. Therefore, these brands can produce”. Natasha Kumar- Food and Drink Analyst, Mintel

Even the largest companies like Amul, Mother Dairy, and Nestle have a tiny percentage of the market, and they have been there for decades (Amul 1946, Mother Dairy-1974 and Nestle-1961). Market research firms Mintel and Euromonitor declined to release market share numbers. However, in the 2016 piece in the Economic Times of India citing Euromonitor put the figure at about 7% for Amul, 3.7% for mother dairy and 2.9% for Nestle. In short, leveraging existing dairy infrastructure is cost-effective but time-consuming. Consider the time and effort involved in contacting dozens or hundreds of local and regional dairies. Whether through processors or sole farmers, establishing a separate supply chain will be costly, as Danone discovered the hard way.

“They bought the cold chain; they bought the supply chain and that’s how they were trying to source their product. That in itself becomes really difficult to maintain. In terms of cost, it becomes really expensive.” Natasha Kumar- A Food and Drink Analyst at Mintel

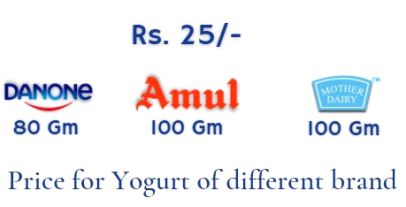

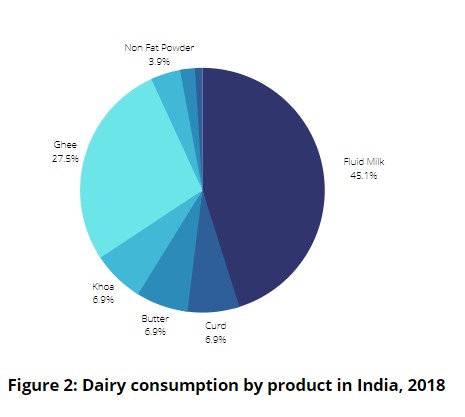

When Danone got the milk, the company focused on the wrong products. Danone pushed plain Yogurt and flavoured Yogurt drinks popular in places like the US and France with high-profit margins to boot. However, at the time Danone arrived in India, yoghurt accounted for only 7% of total dairy consumption. The real money was in Ghee, a type of clarified butter, and plain could fluid milk. A product with razor-thin margin dominated by those hundreds of local small scale producers.

The only way to have significant business in India was if you were selling liquid milk, and liquid milk is a highly, highly competitive market. There are hardly any margins in there. If you’re just selling liquid milk and connecting with local farmers, there’s no way they could have made any sufficient margins to survive as a business. In India, most of the players that are already in the packaged Yogurt business have other businesses which I would say cushion their bottom line.

As per the Analyst, the simple reason why Indian consumers shunned Danone’s per packaged Yogurt. People make Yogurt at home. People make cheese at home, so they don’t buy Yogurt or cheese from outside, they just buy milk and they do it themselves, and they consider it fresh, they can do it well and is cheap. And if Indian consumers wanted to buy pre-packaged yoghurt, they had a plethora of less expensive options than Danone.

Dairy never accounted for more than 10% of Danone's sales in India, a far cry from the company's global 50%. Its specialised nutrition division picks up the slack, and when it closed its dairy operation, the company announced a renewed focus on that division. Meanwhile, Amul and Nestle, two of their biggest competitors, made nearly five billion and 750 million from dairy, respectively. However, the Danone dairy in India is not without hope. In January 2018, at the same time that Danone announced the end of its dairy production there, the company's investment arm announced a $ 26.5 million investment in Epigamia, an Indian yoghurt start-up. This could be a long-term strategy for Danone in India's dairy industry because Epigamia provides consumers with products that add value to the plain yoghurt they can make at home for a low cost. But perhaps most importantly is this; while most of the population still makes Yogurt the old-fashioned way, analysts predict that a growing number of consumers will want to buy premade options as they move into corporate jobs in developing urban centres.

There are certain sections in urban markets where people are educated or people who are working, they don’t run their kitchens the way their mothers used to so they are buying these packaged products. This trend has been picking up very, very quickly still there will be a large section of Indian society where people will take a very long time to convert to ready-made packaged and value-added products. But the one which is converting, even if it is small percentages, they add up to very large numbers. If only 5% of India’s 1.35 billion decides to buy pre-packaged Yogurt, that’s over 67 million consumers- more than the entire population of Danone’s native France which is 66.98 million in 2018.

“Consumers are becoming very busy, and therefore they are looking for that ultimate thing, which is convenience. But having said that. It would not be the typical kind of convenience that you are looking at when you are comparing. It may be Europe or USA because Indian consumers still latch onto authenticity. They gave that typical authentic taste that your mom used to make, for example, so that’s the kind of balance that brands would then probably need to keep in mind” Natasha Kumar- Food and Drink Analyst, Mintel